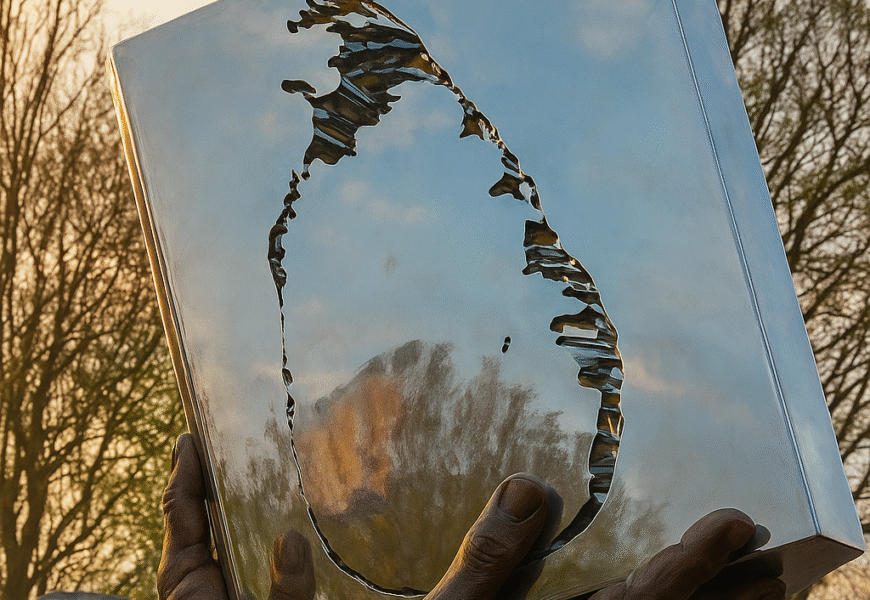

On May 10, in Brampton, Canada, a solemn yet powerful event marked a turning point in the global Tamil diaspora’s quest for justice: the inauguration of the Tamil Genocide Monument. Dedicated to the victims and survivors of the Mullivaikkal massacre—the brutal climax of the armed conflict in Sri Lanka where tens of thousands of Tamils perished—this memorial stands as a symbol of remembrance, resistance, and resolve.

The Mullivaikkal genocide was not just an unfortunate consequence of war. It was a systematic, state-sponsored campaign marked by war crimes and crimes against humanity. In the final days of the conflict in 2009, the Sri Lankan state directed Tamil civilians to so-called “No Fire Zones“, only to bomb those very zones relentlessly. Medical aid, food supplies, and humanitarian assistance were deliberately blocked. Tamils were subjected to torture, sexual violence, enforced disappearances, and extrajudicial killings—atrocities that continue to echo painfully in the hearts of survivors and observers alike.

The Role of Monuments in Collective Memory

Genocide monuments are not unique to the Tamil community. The Tsitsernakaberd Memorial in Yerevan commemorates the Armenian Genocide of 1915, and stands as one of the earliest public acknowledgments of genocide in modern times. Similarly, the Holocaust Memorial in Philadelphia—”Six Million Jewish Martyrs”—unveiled in 1964, was among the first public Holocaust memorials in the United States. These spaces are more than stone and sculpture; they are vessels of memory and agents of moral clarity.

These monuments serve three fundamental purposes:

Remembrance – They honor the victims, giving names, faces, and stories to those who were erased from history by violence.

Education – They act as historical witnesses, warning future generations about the dangers of hate, authoritarianism, and ethnic cleansing.

Justice and Healing – For survivors and descendants, memorials are part of the healing process, providing recognition of suffering and a call for justice.

Genocide Memorials and Global Politics

While these monuments are essential to healing and education, they also carry significant geopolitical implications. A genocide memorial is never politically neutral—it challenges denial, demands accountability, and sometimes strains diplomatic ties.

The Armenian Genocide Memorial continues to be a point of tension between Armenia and Turkey, which denies the events of 1915 constitute genocide. Likewise, as Tamil genocide memorials begin to appear in diaspora hubs like Canada, they inevitably raise questions about Sri Lanka’s conduct, international silence, and the failure of global justice mechanisms.

Such memorials also emphasize the international community’s responsibility under the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted on December 9, 1948. This date has since been designated by the United Nations as the International Day of Commemoration and Dignity of the Victims of the Crime of Genocide and of the Prevention of this Crime. Each year, high-level events reaffirm global commitments to prevent such atrocities—yet, glaringly, the Mullivaikkal genocide remains unaddressed by major international institutions.

Mullivaikkal, 16 Years Later: A Deafening Silence

It has been 16 years since the genocide at Mullivaikkal, and yet the global institutions that proclaim “Never Again” have done little in the way of tangible justice. Investigations remain stalled. Accountability is absent. Survivors still await recognition.

In Tamil Nadu, a memorial in Thanjavur stands, as does one at Jaffna University in Sri Lanka—though the latter has faced state-led attempts to demolish or suppress it. These spaces are fragile yet fierce statements of Tamil resistance and remembrance.

With over 80 million Tamils worldwide, the call is clear: Tamil Genocide memorials must be established across the globe. Not only do they bring visibility to a suppressed history, but they also amplify the ongoing struggle for justice, self-determination, and peace.

Monuments of the Past, Foundations for the Future

Genocide monuments are not relics. They are active spaces—where history, politics, and human rights converge. They challenge the erasure of truth, confront the perpetrators of mass violence, and call the world to a higher moral standard.

From Auschwitz to Mullivaikkal, these monuments teach us that silence is complicity, and memory is resistance. As we move toward a more interconnected global community, establishing, protecting, and honoring genocide memorials is not just an act of remembrance—it is a demand for justice, dignity, humanity and self-determination.

For the Tamil people, these memorials also symbolize a deeper, ongoing struggle: the right to self-determination. Remembering Mullivaikkal is not only about mourning the dead, but asserting the living right of Tamils to define their identity, preserve their history, and shape their political future free from oppression. In this light, genocide monuments become more than spaces of grief—they become beacons of liberation.

Let every stone laid in memory be a step toward a world where no nation is denied its voice, and no people are denied their right to exist with dignity and freedom.