“Mass graves don’t just speak for the dead — they give the living legal leverage.”

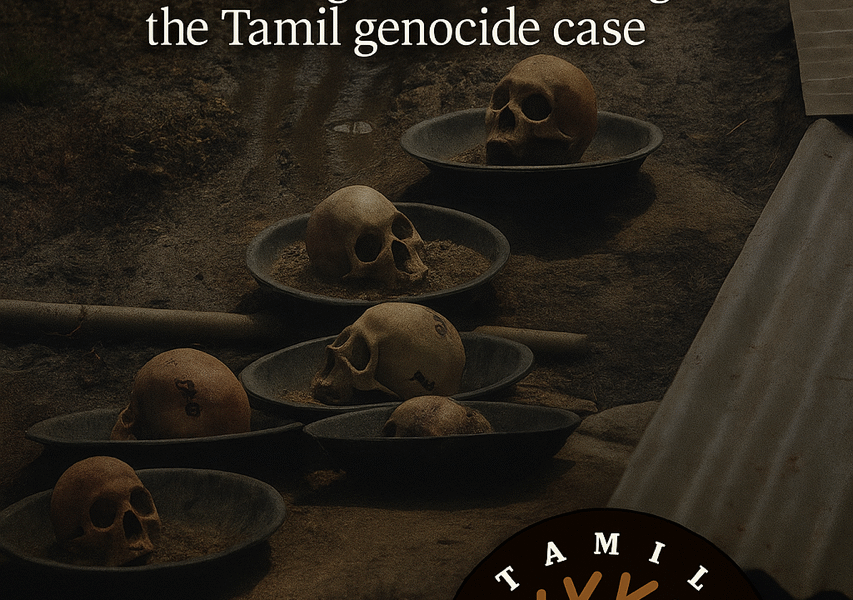

In the scorched aftermath of the Sri Lankan civil war, where nearly 70,000 Tamil civilians were reportedly killed in the final months alone, the soil remains haunted. And now, it may speak again. The recent unearthing of a suspected mass grave in Kokkuthoduvai, Mullaitivu, brings with it not only the remains of those silenced but a renewed legal and moral weapon for the Tamil cause.

The Long Road Through Geneva

The Tamil people’s struggle for justice at the international level has been painstaking and often frustrating. Since 2011, when UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon appointed a Panel of Experts led by Charles Petrie, which concluded that war crimes and crimes against humanity may have been committed by both the Sri Lankan state and the LTTE, there has been a cycle of promises, resolutions, and inaction.

The UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) passed its first resolution in 2012 urging credible investigations, followed by successive resolutions that culminated in the 2014 OHCHR Investigation on Sri Lanka (OISL). A brief moment of optimism came in 2015 when Sri Lanka’s new government, under Maithripala Sirisena, co-sponsored a resolution (30/1) pledging truth-seeking mechanisms and international participation in accountability. But those promises faded quickly.

By 2020, under President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Sri Lanka formally withdrew from its commitments. The international community watched as militarization intensified, land grabs continued, and judicial independence eroded. The 2021 and 2023 resolutions at the UNHRC introduced the “Sri Lanka Accountability Project” and called for enhanced monitoring and evidence preservation. Still, no tribunal, no prosecution, no justice.

The 2025 Mass Grave: A Turning Point?

The recent discovery of a mass grave in Mullaitivu may present a fresh opening. Forensic teams dispatched by the UNHRC to the site in early 2025 have suggested the remains could belong to victims of extrajudicial executions during the war’s final phase. Families of the disappeared are demanding DNA testing, full transparency, and international oversight.

Mass graves, in international jurisprudence, carry weight far beyond symbolism. They were instrumental in convictions in the cases of Darfur, Rwanda, and Syria. Each of those cases had a common trigger: irrefutable forensic evidence of atrocity crimes, and the courage of victims and advocates to transform evidence into legal pursuit.

The UNHRC Stage: Not a Courtroom

Despite the gravity of evidence and multiple resolutions, the UNHRC has limited enforcement power. It can pass resolutions, mandate investigations, and maintain international scrutiny — but it cannot prosecute. More importantly, Sri Lanka is not a signatory to the Rome Statute, meaning the International Criminal Court (ICC) has no jurisdiction unless the UN Security Council refers the case — a near impossibility due to predictable vetoes from Russia and China.

The Rajapaksas understood this. They made symbolic gestures, survived the diplomatic theater, and ensured impunity at home. The Tamil movement’s next steps must pivot from performance to pursuit — from Geneva to The Hague, from resolutions to legal action.

The Case for the UN General Assembly

The Tamil strategy can take a page from the Rohingya playbook. When the Security Council failed to act on Myanmar, the UN General Assembly (UNGA) stepped in. It passed resolutions recognizing the risk of genocide and supported an ICC investigation through a jurisdictional loophole: cross-border crimes committed against refugees in Bangladesh, a Rome Statute signatory.

Sri Lanka, unlike Myanmar, hasn’t even ratified the Genocide Convention (it only signed it in 1950). This closes the door to a genocide case under Article IX of the Convention at the International Court of Justice (ICJ). But it opens another: naming and shaming through a UNGA resolution recognizing the Tamil massacres as a “suspected genocide” — a moral and political step Canada has already taken unilaterally.

Legal Paths Forward: Strategy Over Permission

Sri Lanka’s lack of cooperation does not mean justice is out of reach. Here are viable alternatives:

- Universal Jurisdiction: Countries like Germany, Argentina, Canada, and South Africa allow prosecution of grave international crimes regardless of where they were committed. This route has already produced convictions in Syrian war crimes cases.

- International Treaties Sri Lanka Has Ratified: Sri Lanka is bound by treaties like the Convention Against Torture (CAT) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Violations can be pursued in international forums or through state complaints.

- Jus Cogens Norms: Genocide, torture, and crimes against humanity are considered peremptory norms in international law — binding on all states regardless of treaty status. Legal scholars and advocates can build arguments around these principles.

- Third-State Loophole to ICC: Like the Rohingya case, if cross-border elements of the crimes — such as forced displacement into India or asylum seekers in Canada or the UK — can be demonstrated, the ICC may assert jurisdiction.

- Commonwealth and Regional Forums: Tamil diaspora advocacy can leverage other platforms like the Commonwealth, the EU, and regional bodies to increase pressure and coordination.

Precedents: Where Mass Graves Changed Everything

- Darfur (Sudan): Despite Sudan’s non-membership in the ICC, the UNSC referred the case, citing mass graves as key evidence. This led to the indictment of President Omar al-Bashir.

- Rwanda: The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was established by UNSC Resolution 955 following the discovery of mass graves and overwhelming evidence of genocide.

- Syria: Despite not being an ICC member, war crimes trials have been held in Europe using universal jurisdiction — with mass graves and digital evidence playing crucial roles.

What Will Pressure Sri Lanka?

- UNGA Condemnation: A resolution denouncing Sri Lanka’s refusal to ratify the Genocide Convention would have symbolic power and global resonance.

- Diaspora Diplomacy: Coordinated Tamil advocacy can encourage countries like South Africa, Argentina, or Chile — all with moral authority and relevant legal frameworks — to raise the issue in multilateral forums.

- Conditional International Support: Linking trade, aid, and diplomatic support to human rights obligations — including treaty ratifications — can create leverage points.

From Soil to Summit — Justice Is a Process

As the bones of the war’s forgotten victims resurface, the Tamil movement stands at a critical junction. This is no longer just a story of historical grievance — it is one of forensic truth, legal ingenuity, and strategic persistence.

Genocide may not be formally recognized today. But international law is not static — it evolves, shaped by courage, documentation, and diplomacy. Tamils do not need Sri Lanka’s permission to seek justice. They need a bold, smart legal strategy, a willing partner state, and the will to see it through.

“You don’t need Sri Lanka’s permission to take them to court. You need a smart legal strategy, a willing state, and the courage to pursue it.”

The mass graves of Mullaitivu may prove not just evidence of death — but the long-awaited trigger for justice.